Charles Clay's descriptions of

Yorkshire seals has pictures (you need access to Cambridge Core for this article). One day I might take some pictures myself, but until then, I've shamelessly infringed copyright, I'm sure, but copyright didn't exist in the Middle Ages...

Bertram de Bulmer founded a double house of Augustinian canons and nuns at

Marton in the

mid-12th century. (This

aerial photo shows the farm that it's become, but if you look closely, you can see its outlines.) This wasn’t too far either in time or area from Gilbert’s double house at Sempringham, so Bertram was perhaps following Gilbert’s lead. The nuns, however, quickly moved out, to the neighbouring hamlet of Molesby (the area is now Marton-cum-Moxby). If the 12th-century canons of Marton were anything like their 13th-century successors, the reasons for the nuns moving out would be obvious. In 1280, Marton was in dire financial straits; the prior ‘resigned’, and the Archbishop brought in a new one (from Newburgh) and brought in the Archdeacon of Cleveland to supervise. He also sent some of the brethren off to other monasteries – a bit like moving unruly pupils to another school. Things didn’t improve much in the 14th century. In 1308, the canons elected William de Bulmer prior, but Archbishop Greenfield quashed the election and sent him to Drax. Greenfield’s visitations found a den of iniquity: brother Alan de Shirburn was having it off with three women (one married); brother Stephen de Langetoft had two mistresses; brother Roger de Scameston had five (one married). The brethren tried to elect Alan de Shirburn as prior in 1318, but, unsurprisingly, the archbishop quashed this. In 1321, the Scots raided and laid waste to Marton; the brethren, apart from the prior and sub-prior, were dispersed to other houses (including Bridlington). Marton straggled on till the Dissolution, caving in quite willingly.

Meanwhile, next door at

Moxby, the nuns followed the Augustinian rule, and their house and chapel were under the invocation of St. John the Evangelist and the charge of a local vicar. If Archbishop Greenfield was having trouble with Marton, Moxby didn’t give him much rest, either. Sister Sabina de Apelgarth was in danger of apostasy; the Archbishop instructed the nuns to receive her penitential self back. His visitations of 1314 didn’t dig up the scandals that afflicted Marton, but he did note that they were to stay within the convent (and that included the prioress). The nuns were dispersed by the Scottish raids that did for Marton, and they were sent to Nun Monkton, Nun Appleton, Nunkeeling, and Hampole. In 1325 the prioress resigned because of her affair with the chaplain. The convent was also in debt. And Sabina de Apelgarth was still being troublesome: a brief spell as prioress was ended, for misconduct, by the archbishop. The rest of the life of Moxby was apparently uneventful.

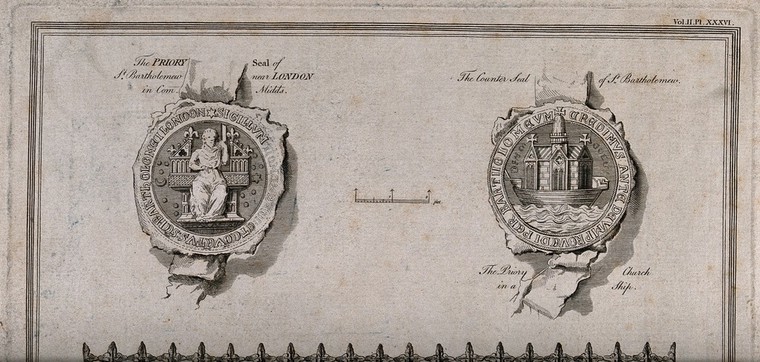

Moxby's seal is quite interesting. It was dredged from the Foss in 1884, and is apparently now at the

Yorkshire Museum. It's late-12th/ early-13th century, and probably depicts Augustine. He's vested for mass, with crozier in left hand and right hand in benediction. The mitre is on at a rather old-fashioned angle, more in keeping with early 12th-century mitres, e.g.

Nigel of Ely. But the cross molines on his chasuble recalls Anthony Bek's (see post on

Gisburne). The cross molines is not the Bulmer arms, and nor does it appear on the seals of the archbishops of York. A bit of a mystery. The inscription is SIGILL': CAPITVLI: SCA N: JOHANNIS: DE MOLESBI.

Clay didn't give pictures of the chapter seal of Marton, but only the seals of Prior Henry (c.1203-27), left, and John de Thirsk (1349-57), right. The photos aren't great. Henry's is a prior with hands on chest; John's is BVM and Child, reversed from the usual way round, within a polylobed vesica, and the prior praying beneath (cf. Merton, Oseney, etc.).

.png)

.jpg)